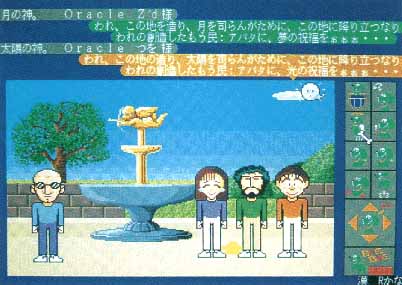

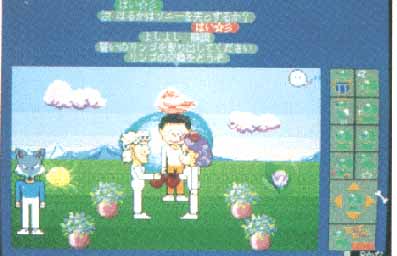

"The world of Habitat is called Populopolis, its inhabitants are Avatars. Players can choose from a large collection of exchangable heads for their Avatar. The basic controls for movement and actionare presented in the menu bar on the right. What is typed on the keyboard appears in a speech bubble above one's Avatar. "

Die Geschichte :

Habitat wurde 1984 für den c64 entwickelt, und kam aufgrund seiner reduzierten Grafik mit der sensationellen Bandbreite von 300 Baud aus. Es gilt als das erste grafische Echtzeit-Kommunikationssystem. Habitat hat inzwischen eine bewegte Geschichte hinter sich. Seit 1988 gehört das System dem japanischen Konzern Fujitsu und läuft in Japan sehr erfolgreich mit mehreren tausend Benutzern. Paralellel dazu gab es bis März 1994 in den USA einen weiteren Nachfolger namens Club Caribe. Seit 1994 betreibt Fujitsu Habitat wieder in den USA unter dem Namen WorldsAway. Das System ist über Compuserve erreichbar.

Habitats Welten sehen aus wie Zeichentrickfilme oder Jump&Run Videospiele. Animierte Figuren die von ihren Benutzern vor gemalten Hintergründen gesteuert werden. Die Steuerung erfolgt per Kommando-Eingabe über die Tastatur, sehr ähnlich den ersten grafischen Adventure Games, aber eben Online, also vernetzt mit der Absicht, in diesem System zu kommunizieren.

Robert Rossney schreibt in Wired über die Erscheinung von WorldsAway : "The screen shows a background that's something like a stage. Click on the screen, and your avatar will walk to where you clicked. Using various menus, you can make your avatar pick objects up off the ground, feed coins into vending machines, and put things in its pockets. Other menus let you wave or smile at other avatars you meet. Anything you type appears in a speech balloon above your avatar's head.

WorldsAway's long history is a little too evident. It looks cool, the background graphics are in a hallucinatory art nouveau nouveau style, sort of Aubrey Beardsley meets William Gibson; but the software feels like something that used to run on a Commodore 64.", und weiter "This may make WorldsAway the most successful example yet of a new species of online service. Part chat room, part adventure game, part puppet show, part simulation, it's hard to know what to call this species. "Avatar-based online shared virtual environment" may be accurate, but it's a mouthful. "Graphical MUD" is a good try, but only if you know what a MUD is. Randy Farmer, one of the original developers of WorldsAway, just calls it "cyberspace," but he faces a lot of competition for this word....."

Whats special about it ?

Zunächst einmal war Habitat "schon immer" da, und es existiert auch immer noch. Die Möglichkeit, Dinge in der Welt zu hinterlassen, die sich auch dann noch an Ort und Stelle befinden, wenn man sich 2 Wochen oder Jahre später wieder einloggt ist Ausgangsbasis für die Enstehung von so etwas wie Kultur. Die Benutzer bilden sich ab, sie hinterlassen Spuren, sie erkennen sich und andere wieder, und instinktiv werden Begriffe wie Besitz und Verantwortung projeziert. Habitat (wie auch die LambdaMOO) haben eigene Gesetze, Benimmregeln, Ordnungshüter und eine Art basisdemokratisches Rechtssystem. Gleichzeitig haben die Entwickler von Habitat auch den nötigen Humor bewiesen, den man benötigt, wenn man keine digitale Schrebergartensiedlung produzieren möchte. Das beliebteste Sammlerstück in Habitat ist der Kopf eines anderen Benutzers. Robert Rossney : "And then there are the headhunters. Buying a head is the most prominent way to assert your identity in Kymer. Your choice of a head determines how other people see you. (It's not for nothing that in wedding ceremonies the bride and groom momentarily exchange heads.) It's no coincidence that heads are among the most expensive artifacts in Kymer's virtual economy of tokens. As objects of great value, heads also attract criminals. The headhunters hang out by the docks, waiting for the boat that brings new users to Kymer. When a newcomer disembarks, the headhunter welcomes him with a friendly greeting. He gives the newbie a few hints on places to go and things to do. Then he moves in.

"Here's something fun," he might say. "Did you know you can take off your head? Try it!"

The newcomer removes his head. "So I can! That's pretty neat!"

"Here," says the headhunter, "let me show you something else. Give me your head."

You would think that most people would have the sense not to give something valuable, like their head, to a complete stranger. Judging from the number of headless avatars I saw wandering forlornly around the streets of Kymer, a fair amount of people do not."

(See Chip Morningstar and Randall Farmer, "The Lessons of Lucasfilm's Habitat", in: Michael Benedikt (ed.), Cyberspace. First Steps, MIT Press 1991)